WATCH AGAIN: NASA's DART spacecraft crashes head-on into a small asteroid

NASA's DART spacecraft crashes head-on into a small asteroid

NASA's DART spacecraft has crashed head-on into a small asteroid to test one of the potential ways to deflect an asteroid when one is headed toward Earth.

NASA's DART spacecraft has crashed head-on into a small asteroid to test one of the potential ways to deflect an asteroid when one is headed toward Earth.

Since launching from Florida last fall, the Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) spacecraft has been traveling toward a binary asteroid system – the larger Didymos and its smaller moonlet Dimorphos, about 7 million miles from Earth. The pair of asteroids are considered near-Earth asteroids because their orbit will one day take the asteroids zooming by Earth but are no threat to our planet.

On Monday, DART used autonomous navigation to hone in on the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos, then charged head first at about 15,000 mph, acting as a battering ram into the space rock.

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) in Maryland manages the spacecraft for NASA, and teams in the APL mission operation center have worked toward this moment for years.

Here's what to expect from the dramatic result of NASA's first planetary defense mission.

The timeline

DART Mission Systems Engineer Elena Adams, with JHUAPL, said the mission operations center, or MOC, was "all hands on deck" 24 hours before impact.

NASA's associate administrator for science Thomas Zurbuchen told FOX Weather on Monday morning the team was excited and ready.

"As always, when you are in these kinds of moments, it's a little bit nervous as well because you think about all the things that could go wrong," Zurbuchen said. "This team has been enormously strong coming together and doing this work here out of Johns Hopkins APL, but also with people around the country to get this mission ready, get it launched during COVID times, when very few missions were launching elsewhere, and having it on a collision course now later tonight."

NASA carried live coverage online and on NASA TV of the impact that occurred just after 7 p.m. (ET) on Monday.

About four hours before impact, DART began to autonomously navigate to its end.

One hour before impact, DART used a relative-navigation system called SMART Nav to hone in on Didymos. Slowly, the smaller Dimorphos came into focus. The spacecraft sent back stunning imagery at about one image per second.

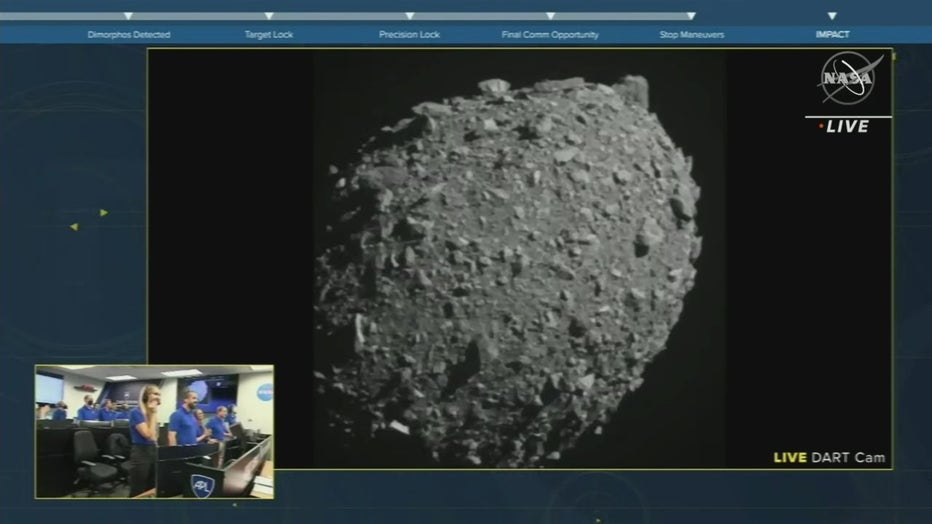

DART then underwent a "precision lock" on its target, ignoring Didymos and zooming toward Dimorphos. About 2.5 minutes before impact, Smart Nav turned off, and DART's cameras took high-resolution photos of Dimorphos before it smacked into its subject.

Dimorphos, only about 530-feet-wide, wasn't in focus and clear until moments before impact. The last image was taken about 2.5 seconds before DART flew into the asteroid. Seconds after impact, DART's team confirmed a "loss of signal" from the spacecraft.

Because of the 8-second delay from DART's signal to Earth, photos continued to come through the mission operations center in Maryland.

What is the goal?

This is the best way to test the kinetic impactor Earth defense theory.

"The point of a kinetic impactor is you ram your spacecraft into the asteroid you're worried about, and then you change its orbit around the Sun by doing that," Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Planetary astronomer Andy Rivkin said.

DART won't change the orbit of Didymos. It aims to change the speed of the moonlet, Dimorphos, by just a tiny percentage, maybe an inch or two a second.

The spacecraft will not change the orbit enough that Didymos or Dimorphos will become a threat to Earth.

How will NASA know if it worked?

The first indication of success was a loss of signal from DART, indicating the spacecraft did not survive the impact.

DART also brought along a companion in the form of a tiny spacecraft built by the Italian Space Agency (Agenzia Spaziale Italiana) called LICIACube.

Three minutes after DART made a direct hit, LICIACube flew by the asteroid to survey the damage. The Italian spacecraft will record the impact area, and debris using two cameras, LUKE and LEIA.

Scientists using ground-based telescopes will be able to monitor the binary asteroid system's orbit, and multiple spacecraft will be watching the crash when it happens, including the James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble Space Telescope, and NASA's Lucy spacecraft.

Zurbuchen said the data from those spacecraft would come back a day or two after impact.

A follow-up European Space Agency mission launching in 2024, called HERA, will visit Didymos and Dimorphos to check the work or DART and see the impact area.