Debate over toll road projects continues to flare

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. - Gaining initial legislative support last year might have been the easy part for controversial and expensive toll-road projects envisioned to cut through more than 300 miles of mostly rural land from Collier County to the Georgia border.

With many environmental and business groups split about the need and purpose of the projects, lawmakers during the 2020 legislative session will start looking at continued funding and accompanying infrastructure --- water, sewer and broadband ---- as tentative alignments for the roads will soon be rolled out.

Senate President Bill Galvano, a Bradenton Republican who made the corridors a priority during the 2019 session, said the roads are “planning for reality,” because Florida continues to attract new residents and tourists.

“We cannot continue to plan infrastructure in reverse,” Galvano said.

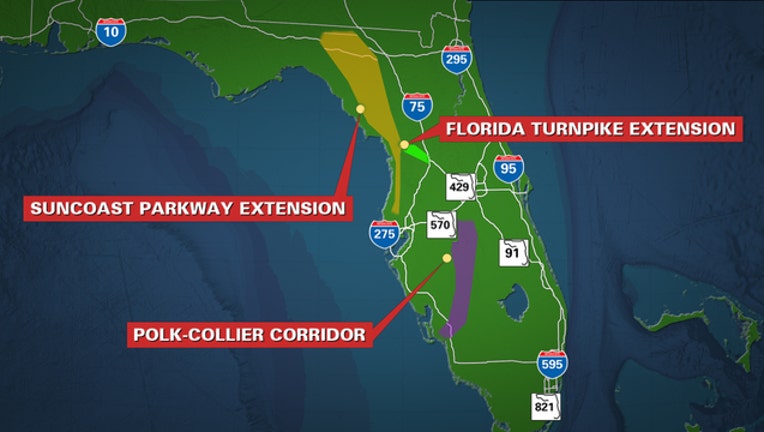

The plan calls for extending the Suncoast Parkway from the Tampa Bay area to the Georgia border, building a toll road from Polk County to Collier County and extending Florida’s Turnpike west from Wildwood to connect with the Suncoast Parkway.

The timeline to start construction on the projects is less than three years off, as the Department of Transportation and task forces work on drawing up plans. Proposed alignments coming from the department are expected to allow the three task forces --- one for each road --- to better find consensus on where to weave lanes around farms, downtowns, natural springs and other sensitive lands. A report must be presented to the governor by October.

The alignments are almost sure to enflame efforts by opponents pushing a “no-build” option. Those opponents repeatedly warn the new roads will cause Broward County-style sprawl for people who want to live in small communities and will devastate already-endangered wildlife.

Neil Fleckenstein of Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy, which owns 9,100 acres in Jefferson County, said more clarity is needed on the “fiscal reality” of the accompanying infrastructure being promised.

“One task force member mentioned, ‘Will every county get a water treatment facility and a wastewater treatment plant?’” Fleckenstein said. “Those are extremely expensive pieces of infrastructure. Tallahassee spent $250 (million), $260 million just revitalizing their wastewater treatment plant.”

Members of the “No Roads to Ruin” coalition, which includes Florida Conservation Voters, Friends of the Everglades, Bear Warriors United, the League of Women Voters of Florida, Our Santa Fe River, Earthjustice and Suwannee Riverkeeper, contend the roads are being driven by business-related special interests and that the money would be better spent on alternative forms of transportation. If traffic warrants the work, they argue the state should focus first on expanding existing roads.

Gary Cochran, a retired state land conservation and planning administrator now with the Big Bend chapter of the Sierra Club, said he’s never seen a transportation corridor or toll-road project that would benefit the environment.

“Yes, while it is true that these projects must mitigate for the taking and impacts on the environmental resources and public conservation lands within the projects scope, that mitigation does not improve the environmental resources, it does not prevent the destruction of those resources, or the bifurcation of wildlife habitats, the destruction of wetlands. It only mitigates, it does not replace the resources lost,” Cochran said.

Groups such as the Florida Chamber of Commerce, Associated Industries of Florida, the Florida Ports Council and the Florida Trucking Association are backing the roads.

Sally Patrenos, president of the Tallahassee-based Floridians For Better Transportation, considers the roads and accompanying infrastructure the most “forward-thinking” initiative in decades by the state.

“In the next five years we’re going to gain another 5 million people, all using the same infrastructure we have in place if we don’t look forward,” Patrenos said. “Infrastructure that is thoughtfully planned and responsibly built can go a long way in keeping pace with our exponential growth.”

Better defining the road locations should also heat up campaigns for and against the projects from communities that could be affected.

The biggest fight could be over the corridor from Polk County to Collier County, which would run through environmentally sensitive areas and has unsuccessfully been sought in the past as the Heartland Parkway.

But communities that could be involved in the other projects also are starting to choose sides.

At the north end, at least some leaders in Jefferson County are lambasting the prospects of the road.

Monticello Vice Mayor Troy Avera, whose family runs a bed and breakfast, said a fear in the community is that the extended Suncoast Parkway would bypass the downtown area.

“Intuition and experience tell me that a bypass of a small town will suck the life out of it,” Avera said. “All our businesses in Monticello depend upon traffic.”

Avera, who is concerned the city budget would suffer a drop in revenue, suggests the corridor should end at Interstate 10 until traffic warrants more northern work. Interstate 10 is several miles south of downtown Monticello.

Less than 20 miles to the east, in Madison County, Greenville Town Manager Edward Walker Dean said his impoverished community would take the road if its neighbors in Jefferson County don’t want it.

“I’m looking at this toll road as being something that will change the plight of this community, bring some new energy in here,” Dean said. “I don’t think the rank and file of these communities really, really know and understand, and there is a natural inclination --- anytime (you are) talking about something that is big, is robust, you have to be a visionary. Greenville is the kind of place that could benefit tremendously. Get a Busy Bee’s (convenience store) or something like that in here. You can work to build something sustainable over time.”

Michele Arceneaux, a Monticello-Jefferson County Chamber of Commerce board member, said Madison County and others that envision the road as an economic panacea should be careful about what they want, as no matter how close to a downtown the corridor is located, motorists will favor franchised businesses at interchanges.

“Limited access roads do not bring meaningful jobs, unless you think fast food and gas stations are quality economic development,” Arceneaux said. “And I-10 is the perfect example of this. The minimum-wage jobs associated with I-10 were at the expense of local business in our downtown.”

The corridors, which received first-year funding of $45 million during the 2019 session, have been promoted as providing more emergency evacuation options, along with handling the state’s expanding population.

Annual funding is projected to reach $140 million by 2023 and to continue through 2030, totaling $1.1 billion. Critics contend the cost estimates are low.

For lawmakers who must annually approve the funding, the focus during the 2020 session, which begins Tuesday, will be the accompanying water, sewer and broadband systems, which have been touted as benefits for rural communities.

Galvano said the projects won’t destroy the environment, and more people will understand the opportunities available as the designs come to fruition.

“The population is going to continue to grow,” Galvano said. “The need will continue to be there. And if we’re forward-thinking, we’ll actually have a net benefit to the environment, whether it’s focusing some of our mitigation opportunities on conservation and even coastal resilience, looking for innovative components to these infrastructure programs, autonomous and other type of mass transit opportunities. It’s a planning for reality and not just throwing up opposition, because folks are coming.”